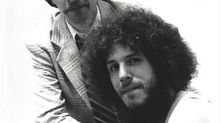

Remembering Hippie Nation (An excerpt from The Backstage Man)

“Never worry about being an outsider. You’re on the inside. Everyone

else is lookin’ in.”

– The Backstage Man

I turned 14 in 1969. That’s right. 1969!

I can’t remember the first “hippie” I ever saw. But they had begun to show themselves on stoops, in parks and on street corners in towns everywhere, and Parkchester was no exception. They were blown free from the post-war American landscape and came floating across the nation, dandelion-like, sowing a mysterious sensibility that lay, tantalizingly, just

out of my grasp.

I saw one hitchhiking down Metropolitan Avenue. There was another playing harmonica on the hood of a car. Two more acknowledged one another as they crossed paths in the street, a winking allusion to some shared secret.

They were young men, they were girls, some just older than I. They seemed full of independence and conviction, poetry and passion. They were dressed, not as their mothers dressed them — and not as their fathers dressed — but in the manner of troubadours and outlaws. They played Robin Hood to the Sheriffs of Nottingham who were our parents, teachers and politicians (otherwise known as “the establishment,” or “the system”).

Their clothes were wonderfully artful. Out of nowhere, these young people had developed an incredibly complex aesthetic, building their uniforms from an astonishing vocabulary of accessories. From an antique cigarette case to an ornate walking stick, from a hand-made belt or bandanna to a grandfather’s pocket watch, most carried something that would distinguish them — with logo-like clarity — from their fellow travelers. I recognized these heavyweight trinkets as the religious artifacts they were, icons of quality and authenticity in a mass-produced and disposable world.

All of this was lost on the American establishment – including just about anybody over 30 – who, incredibly, protested that the hippies all looked the same — a grossly unobservant perception that emphasized the dullness of grownup sensibilities. Yes, most hippies wore jeans (usually bell-bottoms) just as most oil painters began with a canvas. But the jeans were living things, evolving works of art that took on the shape, character and expression of the people wearing them.

The bottoms of the pant legs were tattered from scraping the pavement (clearly a travel record); the denim was worn and threadbare to varying degrees (a litmus test of life experience), and then elaborately patched with an evolving tapestry of fabrics.

Some young male hippies who were lucky in love sported elaborate embroidered patches

which had been contributed by hippie girls (“chicks”) who understood the culture of jeans and knew that it was an honor to send a piece of unique artwork out into the world on some guy’s otherwise threadbare ass. These were coats of arms.

What adults saw as slovenliness and rebellion for rebellion’s sake, I regarded as nothing short of folk art and intellectualism. Yes, the hippies all had long hair. But no two heads of hair were the same, which was, in part, the point. Still more to the point, in my mind, was how these flowing heads stood in dramatic contrast to the severe, chopped-off haircuts of the day, like a meadow beside a sharply manicured lawn; like a lion beside a chihuahua; like a weeping willow beside a tree stump.

Suddenly, short haired people looked like victims to my young mind; they were allowing someone (the establishment? the majority? the neighbors?) to scalp them, to mutilate and humiliate them. In short hair, I saw not only bad fashion sense, but cowardice, because these poor slobs didn’t have the guts to buck the establishment and cover their big goofy ears.

Which meant that these hippies — these lions — were more than majestic. They were courageous. And they had the women to prove it. Don’t tell me no. I saw the incredible young girls — beaded, barefoot and free — who accompanied these new heroes. They had flowers in their hair and sun in their eyes. Girls with names like Heather and Rain … girls who embraced

pre-marital sex, and traveled by thumb. What alternative could parents or teachers possibly have offered to Heather and Rain?

Well, let’s see. You could spend eight hours a day studying bullshit with a hair cut that made you look like a ventriloquist’s dummy. Fuck that! There was nothing to be decided. If you were like me, you were joining these guys — these lions who walked fearlessly among the fearful, casually among the rigid, comfortably among the awkward, seizing the day that others — tragically — failed to notice.

The point is, we only had one life to live. We weren’t gonna do it looking and feeling like Dick Nixon.

***

I could tell you about those years . . . hitchhiking across America; stumbling onto spontaneous parties at stranger’s houses or in vans lined with shag carpeting; living for more than a month in a wrecked boat on the beach; sleeping in parked cars and garages and fruit stands; cavorting with street people, panhandling for breakfast, playing harmonica for nickels and dimes . . . All around us, in slow motion, beautiful young girls tumbling onto their backs like a shower of paratroopers, or polynoses floating down from the tree tops. (The sexual revolution had arrived and I was happy to do my part.)

I knew a man who called himself Moondoggy and one who called himself BarBar. I knew Shamus – a fifty-six-year-old leprechaun – who lived in a shack and did odd jobs out of his pick-up truck. I knew Valarius, a guy who always wore roller-skates and a Viking hat and recited spontaneous poetry. I knew drug dealers, convicts and lunatics, many of whom I loved and admired. I knew a poor man of great girth named Brother John who swept floors to scrounge money for food – yet wore enormous gold rings and walked with a gold cane; and James and Wendy who knew everything and never had to be anywhere except precisely where theywere.